What does “crawl” mean?

Before we get started, we should probably clarify: what does it mean when Google crawls your site? Google crawls all pretty much all publicly-accessible websites. This is a search-engine’s process of finding your site’s links and URLs, and indexing them for others to find. Generally, search engines listen to rules you set in your “robots.txt” file. In WordPress, you can allow search engines or discourage them on your Settings > General settings screen. After you’ve launched your site, you’d generally want Google to crawl their site.

What if I don’t want Google to crawl my site?

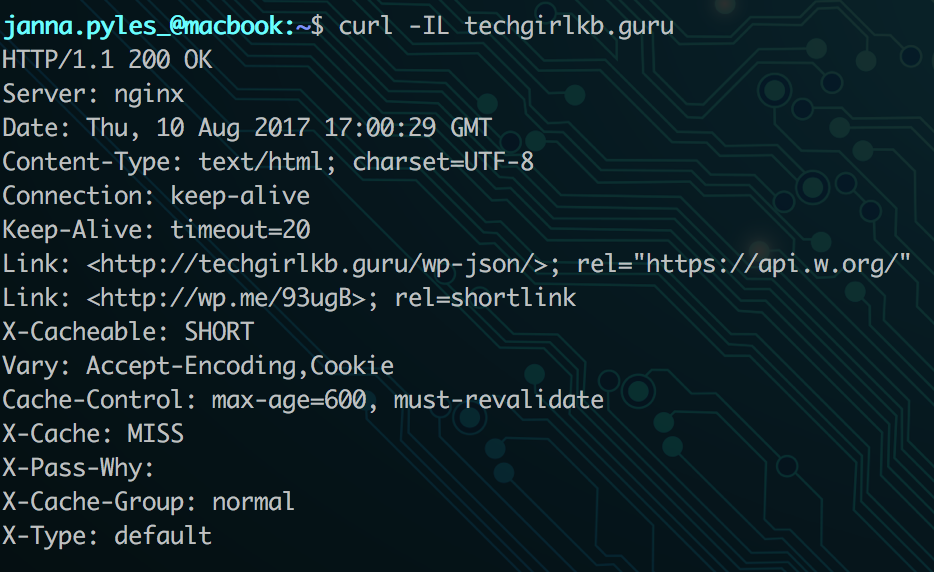

The one exception is if your site is not public to all web users. It technically is possible for Google to crawl a non-publicly accessible site. This generally happens if a link to that site appears on another site which is publicly accessible. In this case, you can request the URL be removed. Remember, this is temporary. So you still need to update your preferences to tell Google not to crawl at all. In the 90 days between the URL removal and reindexing, you need to be sure to add a noindex header or meta-tag to ensure it’s not indexed going forward.

When would I want Google to recrawl my site?

There are potentially a lot of scenarios when you’d want Google to take another look at the URLs that exist on your site. Some common examples include:

- You’ve recently rebuilt or restructured your site

- You’ve added a large number of redirects on your site

- You’re seeing a lot of 404s reported in Google’s Webmasters Tools

- You’ve been hacked or compromised and some bad URLs got indexed

- Google crawls or indexes links that don’t exist

In these cases, it would be appropriate and advisable to ask Google to recrawl.

How do I ask Google to recrawl my site?

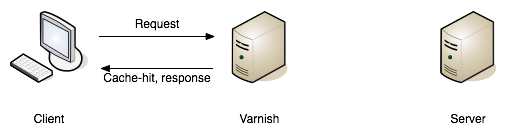

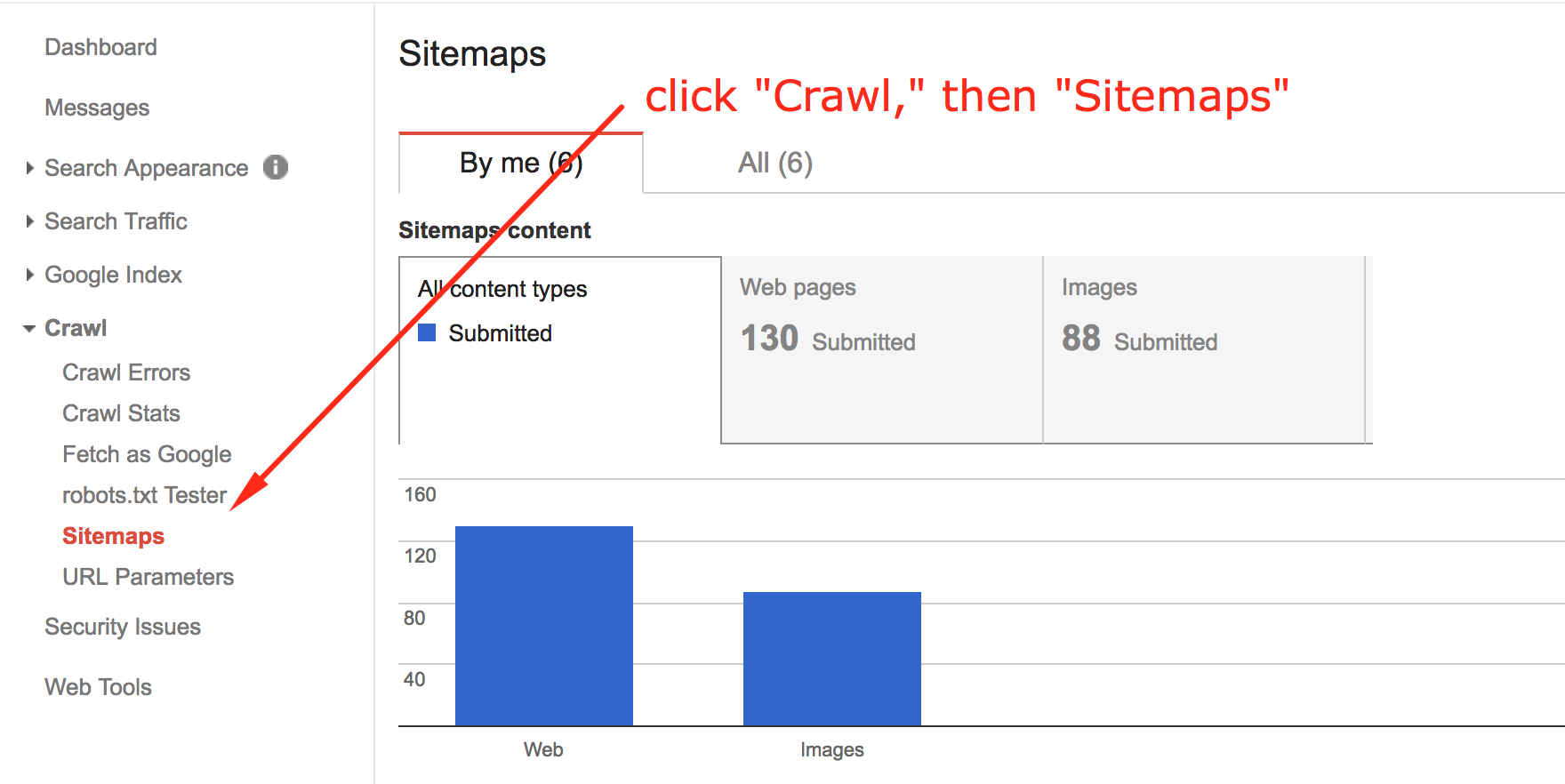

First, I’d recommend updating your sitemap is current, and submitting that to Google. Remember: if you use Yoast SEO, the plugin updates your sitemap as you go. Once you’ve confirmed your sitemap is up to date, be sure to add it to Google (and remove any old ones).

Be sure to click any old sitemaps in the list, and remove them before continuing.

Be sure to click any old sitemaps in the list, and remove them before continuing.

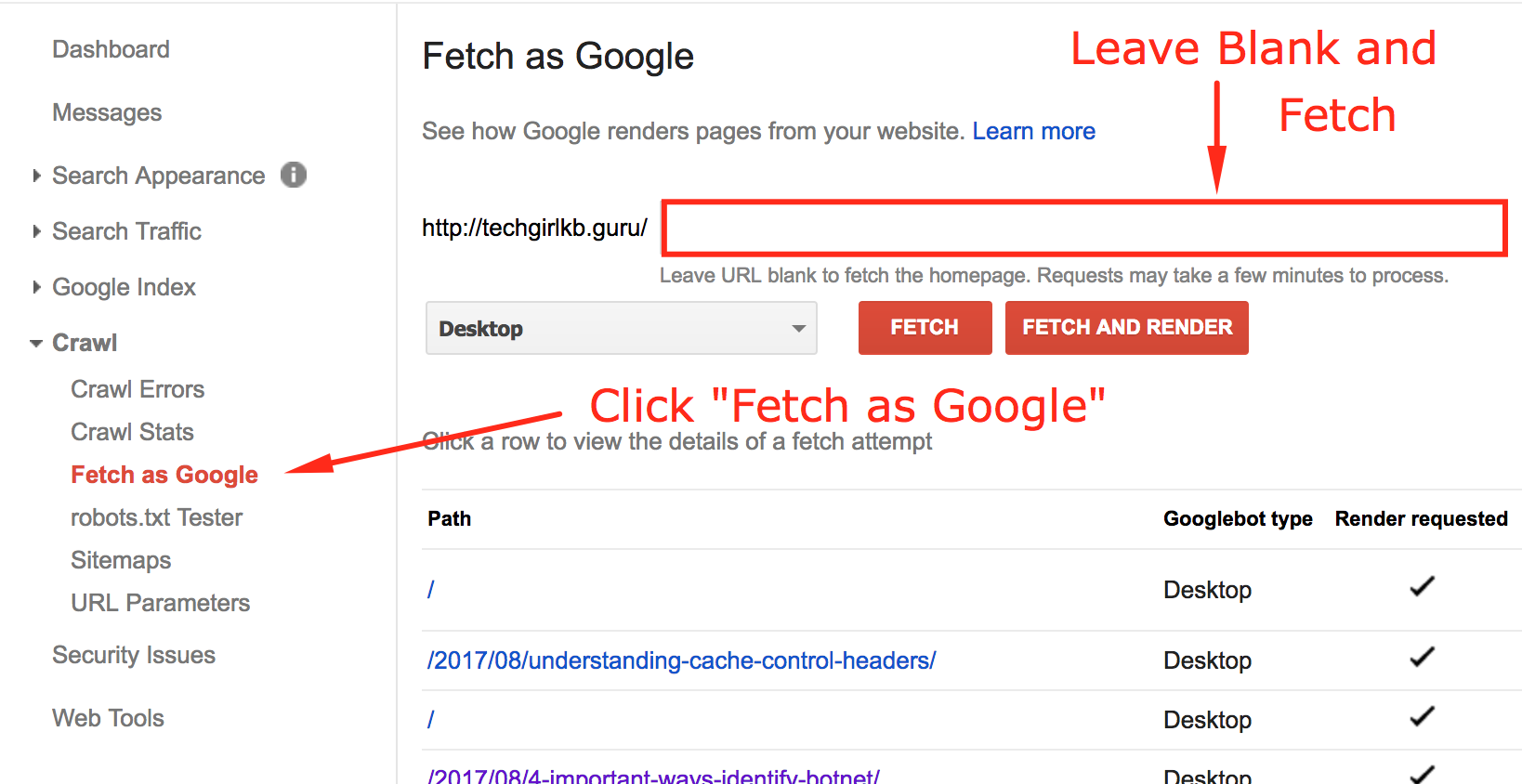

To ask Google to recrawl from here, you can follow these steps:

- Go to Google Webmasters Tools and sign in.

- Select the site you’d like to recrawl from the list.

- Click “Crawl” from the menu on the left.

- Click “Fetch as Google.”

- Leave the box empty and submit.

- Wait a few seconds as Google fetches and renders your site.

- When it finishes fetching, click “Request indexing.”

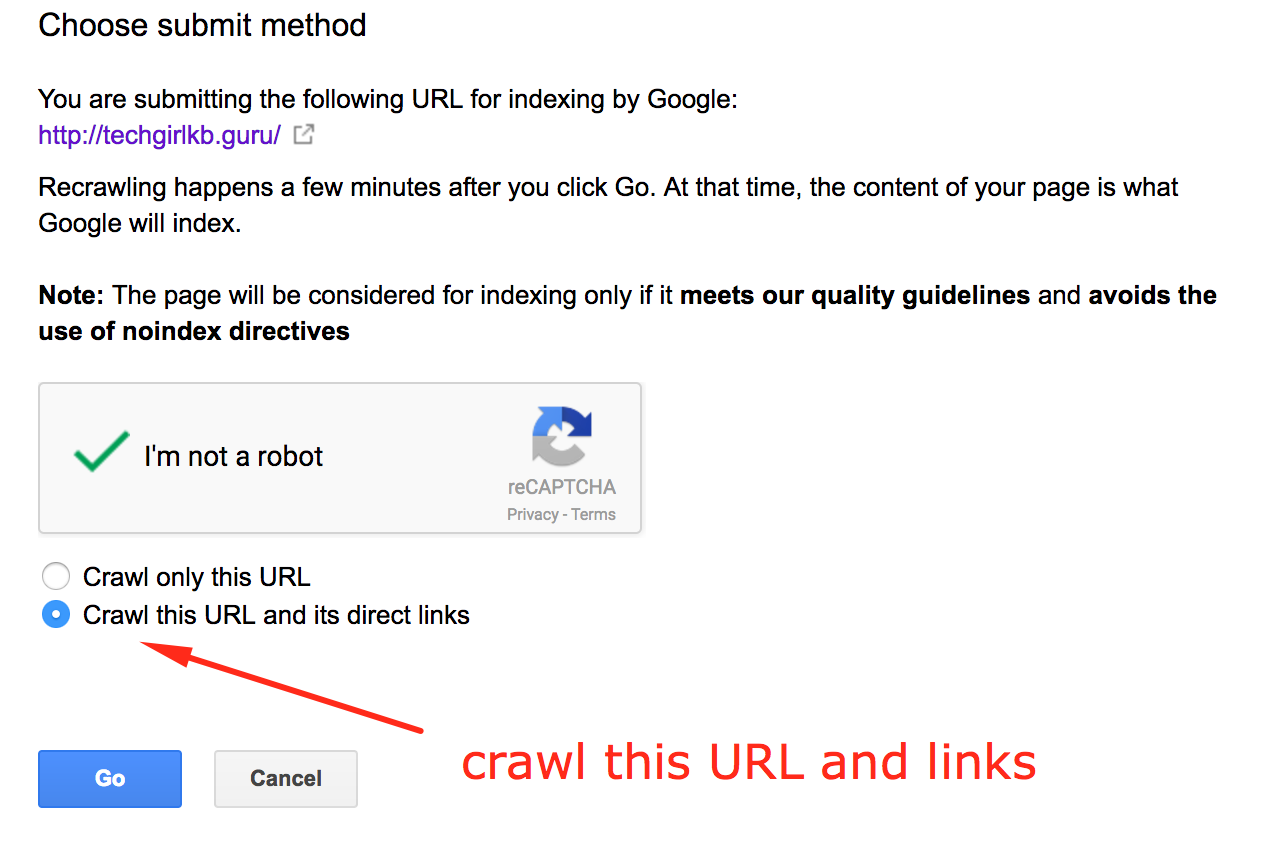

- In the popup window, click “Crawl this URL and its direct links.”

- Wait for a few days – Google usually takes several days to recrawl URLs submitted.

After these steps, the search engine results for your site will be more accurate! However, you’ll want to be sure you allow Google several days to do the recrawl.

That’s all, folks! If you’ve followed the above steps, you’ve successfully asked Google to recrawl your site. Future Google crawls should be more successful too, with your updated sitemap. Additionally, you can find instructions for other search engines online.

Have any other thoughts or advice on how to get Google to recrawl your site? Leave me a note in the comments, or contact me.